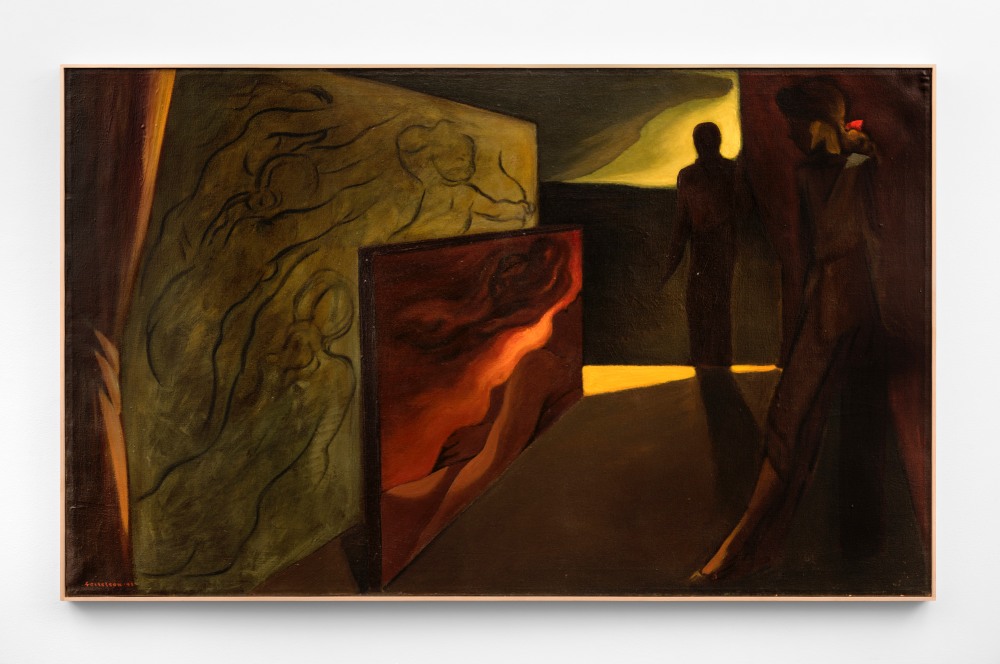

Lorser Feitelson

Paolo and Francesca, 1943

oil on canvas

36 1/2 x 60 1/4inches; 92.7 x 153 centimeters

LSFA# 00356

Even if you’re not familiar with the name Lorser Feitelson, chances are you’ve seen his work. One particular painting of his that struck me when I first saw it six years ago was Life Begins, found in the permanent collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). I was immediately drawn to this oddly shaped canvas marked by a mysterious, entrancing, deep blue background and unexpected mix of collage and painting. It depicted a surrealistically-rendered painting of a halved peach and pit alongside two black and white photographs: one, a long-exposure of a nebula in space and the other depicting a newborn baby, just birthed. The second is sourced from a photograph also entitled Life Begins, which was the first photograph printed in the very first issue of LIFE magazine. In his attempt to capture the inexplicable essence of “life” in all of its awe and wonder, Feitelson’s work felt almost metaphysical. It was exciting—modern—cutting edge, even. I was even more surprised (and elated) when I looked at the date: 1936.

Since then, Feitelson’s Life Begins remained etched in my brain. As life went on, that painting sat quietly in the back of my mind only to be rediscovered this month while doing research related to a new exhibition at Louis Stern Fine Arts. Not unlike my unexpectedly meaningful encounter with his work at LACMA, Feitelson somehow magically found his way into my consciousness once again.

Feitelson was an incredibly influential figure in the California art scene. His revolutionary work dating to the '30s at LACMA was part of his post-surrealist period, a movement he founded in 1934 with his student, Helen Lundeberg (whom he later married), an important figure in his life and artist in her own right.

Recognized as one of the first organized responses to European Surrealism in the United States, Post-Surrealism was a movement in which Feitelson sought to unite the Neoclassicism he found and loved in Paris with metaphysical subject matter championed by the surrealists. Unlike the surrealists’ use of automatism to explore the depths of the subconscious, however, the post-surrealists consciously created associations in their work that were calculated for comprehension. They guided the viewer towards a particular meaning, often an expression of wonder about the natural and cerebral world. Feitelson’s Life Begins proved exactly just that.

The dreamy movement of Post-Surrealism was short lived, however. Together, Feitelson and Lundeberg would later become the faces of a more widely recognized, artistic movement called Abstract Classicism (a term used to distinguish these Southern California artists from the nearby abstract expressionists in San Francisco). The abstract classicists championed the geometric color forms that became so quintessentially “California” during the midcentury. Also known as “hard edge” painting, these are the types of works Feitelson is best known for today: seemingly less complex and philosophical, colorful, abstract forms produced during the 1950s and 60s.

Turns out, Feitelson appeared to have a third stylistic period existing between the two major movements. At the tail end of his post-surrealist work and before he moved into Abstract Classicism, Feitelson engaged in what has been referred to as a “Romantic period.” It was a time when he merged his post-surrealist framework with a deeply personal subject matter: his love life. Whereas his post-surrealist works of the 1930s explored the mysteries and wonders of the natural world and his later “hard edge” paintings removed any sense of subjectivity all together through abstract, geometric forms, neither of these movements really allowed Feitelson to reveal all that much about his own life. The subject matter was removed from the artist and perhaps he wanted it that way. Feitelson’s Romantic paintings, however, may represent the only period of time in which the artist turned inward and reflected that on the canvas, completing works that were not only deeply personal, but autobiographical in nature.

A current exhibition at Louis Stern Fine Arts presents a selection of these paintings from Feitelson’s self entitled, Allegorical Confessions, a moody and sensual, figurative wartime series that relates the artist’s own psychological torment while navigating what appears to have been a quite complicated love life. Exploring allegorical themes relating to lust, chastity, forbidden and unrequited love, this series abounds with drama, romantic intrigue and a curiosity for what lurks beneath the shadows of desire.

In presenting this lesser known, self-referential series, this exhibition offers a glimpse into a rare, figurative and deeply personal period of Feitelson’s work and presents a unique opportunity to get to know the famed, California artist on a more intimate level. Because of this dramatic shift in style and subject matter, upon viewing the exhibition one can’t help but wonder: what exactly was going on in the artist’s life at this time?

Painted between 1943 and 1945, Feitelson’s Allegorical Confessions represent an almost therapeutic working out of the complex, romantic entanglements the artist involved himself in, including his relationship with Lundeberg, whom he met while teaching at the Stickney Hall School of Art in Pasadena, amidst an affair with another woman and failing marriage coming to an end.

However salacious his love life, the exhibition makes one thing clear: Feitelson and Lundeberg’s relationship was one that transcended the boundaries of traditional, romantic love and very much flowed into career and artistic fulfillment as well.

Several paintings in this series reflect the complexity and depth of their relationship. With light blonde hair, a delicate nose and bright blue eyes, Lundeberg’s presence is unmistakable as she appears to be a major figure in many of these paintings. Paintings such as The Leaf (1944) illustrate one of the sunnier moments of the artists’ relationship in which Lundeberg is depicted adoringly sheltering her eyes from the sun while enjoying an afternoon in nature with the artist. A painting and easel lurk in the background, hinting at the notion of burgeoning artistic collaboration between the two. In other works, Feitelson is removed entirely while Lundeberg and her artistic talents are brought closer into view. Paintings such as Three Girls (1943) depict Lundeberg showing one of her post-surrealist paintings, The Pier, to two other women, perhaps demonstrating his respect for Lundeberg as an artist and pointing to her own contributions to the artistic movement.

Other paintings such as Paolo and Francesca (1943), and Beach Nocturne (1943), suggest the complexity and difficulty of maintaining a relationship with Lundeberg that began as an affair between a teacher and student. Marked by tension inducing angles, dark shadows and hints of suggestive red, these paintings are representative of the lust and forbidden love endured by the artists, who were also most likely chastised for having an affair while Feitelson was still married.

Paolo and Francesca (1943), which represents the famous allegorical tale of forbidden love, notably reflects the stylistic influence of the European surrealists and metaphysical painters such as Giorgio de Chirico, whose paintings Feitelson would have seen not only during his time in Europe, but also at the Hollywood home of his friends and collectors, Walter and Louise Arensberg.

Others like Leda (1943), a reference to the allegory of “Leda and the Swan” in which Leda is attacked and seduced by the swan, and Allegory (1945) most successfully illustrate the temptation of romantic desire experienced by the artist during this period. Although it’s unclear at which point Feitelson picked up another affair, Feitelson paints his “confessions” to come to terms with his own infidelity: if not with Lundeberg, most definitely with his wife, who purportedly refused to grant him a divorce for quite a long while after the artist began his relationship with Lundeberg.

This figurative period of the artist ended in the mid-1940s, around the time when Feitelson became increasingly interested in abstraction. His first series of abstract paintings entitled Magical Forms were completed in 1944. By the early 1950s, Feitelson was fully engaged in the style of “hard edge” painting he became so well known for. Alongside artists Karl Benjamin, Frederick Hammersley, and John McLaughlin, Feitelson’s work was shown in the landmark exhibition Four Abstract Classicists which opened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in July of 1959, before traveling to LACMA later that year. The same exhibition went on to the Institute of Contemporary Art in London and Queen’s University in Belfast under the title West Coast Hard Edge in 1960.

Never returning to his Romantic style, Feitelson ended his career fully immersed in Abstract Classicism and never looked back. This exhibition, Lorser Feitelson: Allegorical Confessions, 1943-45, celebrates a brief period of work from the artist that is perhaps often overlooked yet ripe with valuable insight into the artist’s life. While this series may not be the artist’s most well-known works or period of production, this exhibition proves that sometimes, between the beginning and the end, there often lies a little bit of magic in the middle.